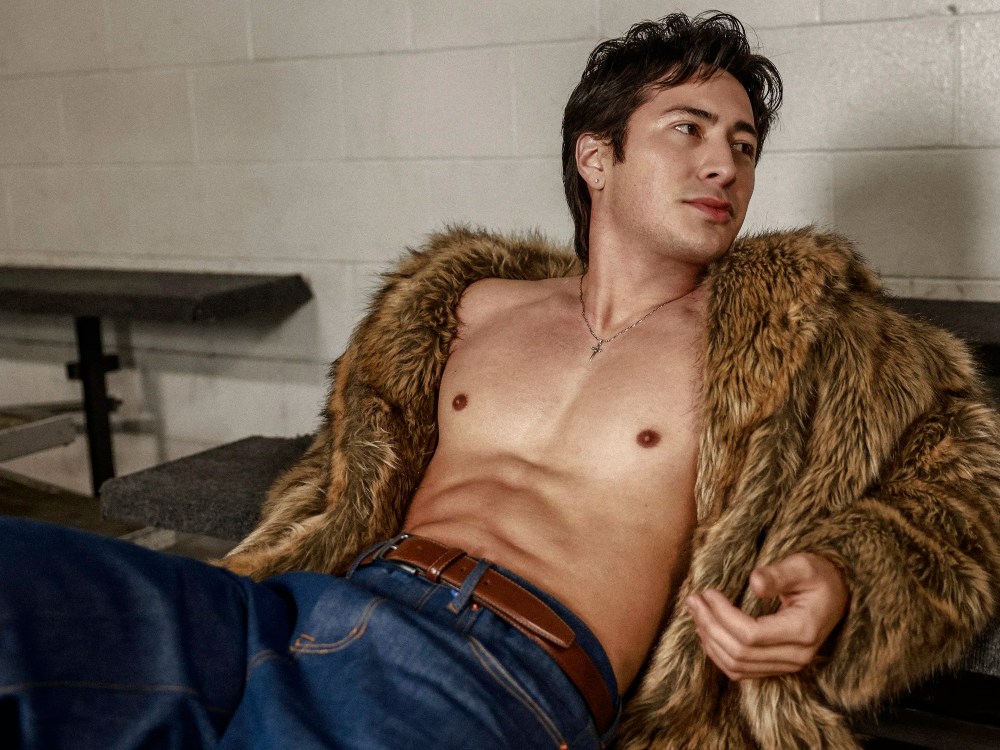

Sunday Star Times’ Chief News Editor Craig Hoyle takes us through his incredible journey of being excommunicated from his family and friends in the Exclusive Brethren church to rebuilding his life, free to live openly as a gay man.

What was it like to grow up in the Exclusive Brethren?

Growing up in the Exclusive Brethren was tightly controlled, with every part of our lives under church influence. All my friends, all my family, my job, my high school – everything was connected to the Brethren, and we weren’t allowed to socialise with outsiders. Looking back, it was a very narrow existence. We called non-Brethren ‘worldlies’ and were taught that they were a lower class of people than us. Anyone who was different was bad. TV was banned, radio was banned and we weren’t allowed pets. That rule came in in the 1960s, when Brethren disposed of their pets en masse. My grandma’s family drowned their cat in the river. It was unthinkable that you’d challenge or disobey a church order.

When did you start to realise you were gay?

Ironically, my first awareness that I might be gay was when the Exclusive Brethren campaigned against the civil union bill in 2003. I was around 13, and up until that point, I knew I was different from the other boys but didn’t have the language to articulate how or why. It was a two-step realisation: firstly, that there was a word ‘gay’ that described how I felt, and secondly, that this was a very bad thing for a Brethren person to be. The Brethren were holding prayer meetings, lobbying politicians and generally being incredibly homophobic. I knew I had to keep this dark secret to myself.

Who was the first person you told about your sexuality, and at what stage did the church find out?

The first person I eventually told was one of the local priests in Invercargill. The Brethren had a confession system similar to the Catholics where you were supposed to reveal all your sins to priests, and I’d been going through the process because I believed it would bring me closer to God. In the end – out of desperation – confessed I was gay at 18 because I believed that was my biggest sin of all.

I understand the Church put you through conversion therapy. What form did that take, and how did you cope with it?

The priests were more sympathetic than I’d expected. The Brethren had moved on from the days when being gay got you immediately excommunicated, and by that point, they were trying to ‘help’ gay people in the church. Help, of course, meant conversion therapy. I saw Bruce Hales, the Brethren world leader, in December 2007, and he told me to never accept myself for who I am. He recommended I speak to a Brethren doctor (who was also his cousin), which I did. That doctor grilled me about my sexuality, including very inappropriate questions such as whether I was sexually attracted to one of the local priests. I felt dirty and tried to run away after that, but failed, and ended up back in the church and being sent to live in Sydney for a while, which is where Bruce Hales lives. In Sydney, he sent me to see another Brethren doctor, and this doctor prescribed a hormonal suppressant called Cyprostat that shuts off the body’s supply of testosterone. It’s usually used for cancer patients and sex offenders. The doctor’s reasoning was that while he didn’t yet know of a way to effectively change someone’s sexuality (although he said he was experimenting with different drugs on other young Brethren people), he could prescribe medication that would help shut down my sexual urges in the meantime. He gave me enough repeats to keep taking the drug for a whole year without seeing another doctor. I started taking the drugs that same day. It was unthinkable that I wouldn’t. I was seeing the doctor on the orders of Bruce Hales, who we believed was literally God’s voice on earth, so disobeying Bruce would’ve been like saying ‘fuck you, God’.

What led to your excommunication?

Following my time in Australia, it became clear that there was no future for me in the Exclusive Brethren. None of their attempts to change my sexuality had worked, and I realised the only way I could stay in the church was to suppress who I was for the rest of my life. That sounded like hell – even worse than the hell the Brethren kept preaching about. I knew I had to leave. It was a massive decision to make, as leaving the Brethren means losing literally everything – your family, your friends, your job, your home… You come into regular society as a refugee, and for the Brethren, it’s as though you’ve died. It’s more extreme than that, actually. They scrub you from their photos and records, and it’s as though you never existed. So deciding to leave was not something that happened lightly.

I’d stopped taking the drugs by this point (the side effects were horrible) and started laying the groundwork for leaving. It’s the things you don’t necessarily think about, like making sure you have copies of photos and medical records, because there’s no way of going back for them once you’re out. And for me, it was important that I saw people I loved one last time. In the weeks before I announced I was leaving, I drove the length of New Zealand, visiting people like my grandma. It’s a crushing feeling, hugging people you love and knowing it’s probably the last time you’ll see them.

The Brethren have two stages of excommunication. The first is when they ‘shut you up’ – a form of religious quarantine – and you’re banned from going to church or talking to other Brethren. The second is when they ‘withdraw’ from you – a final excommunication where they officially wipe their hands of you. The first stage for me happened after I came out as gay to my six younger siblings. The priests called it ‘defilement of young people,’ and that night my brothers and sisters were removed from the family home. I woke up in the morning, and they were gone. No chance to say goodbye, and my parents refused to say where they were. Mum had always said she’d never throw me out, but this put her in an impossible situation. She knew she wouldn’t get her other six kids back unless she cut ties with me. When they were throwing me out, I asked her, ‘How could you do this?’ Her bleak reply was, ‘What choice did I have?’ She looked so crushed.

The local rainbow community in Invercargill was a huge support as this was all happening. I’d reached out and asked for help, and a couple – two girls, Courtney and Mel – offered me a place to stay while I got back on my feet. It was overwhelming coming out into regular society and learning things like how to use a TV remote. I had no idea how to eat at a restaurant! Fortunately, the new friends I made were generous in teaching me how to live in the world. I refused to talk to the Brethren priests after that, and when the final excommunication happened on Halloween 2009 (haha), I’d already started moving on with my new life. I’d lost everything and everyone, but still, being out of the Exclusive Brethren and free to live my life as an openly gay man felt like a huge weight had rolled off my shoulders.

You are now the Chief News Director for the Sunday Star-Times! Can you tell us a bit about your journey from excommunication to now?

I never thought I’d be a journalist. A few weeks after my final excommunication, I was contacted by 60 Minutes reporter Sarah Hall, who was investigating the Exclusive Brethren. She ended up producing a documentary about my story, and the 60 Minutes team was super supportive. They asked what I wanted to do with my life, what I was passionate about and suggested that I consider journalism. They even offered to back me into university. I went travelling for a bit to see the world, and after a year, I came back to NZ and took them up on that offer, and they gave me a part-time job at TV3 while I was studying. Within two years, I went from never having watched TV to working in a TV newsroom – it’s wild looking back!

Sarah Hall was hugely supportive of my career in journalism. She and her husband, Grant, became my de facto parents in the outside world. Sarah wrote to my mum and even went and knocked on my parents’ door in Invercargill to tell Mum that I would be okay. She felt very strongly that the way the Brethren were treating young gay people was cruel and wrong, and she supported several others to leave after me. Sarah has always been an inspiration to me for what journalism is about – it’s not just about telling stories; it’s about putting a spotlight on injustice.

These days at the Sunday Star-Times, my job mostly involves managing our team of reporters and deciding what goes in the newspaper each week. We’re part of Stuff, which employs hundreds of journalists, so it’s a very large machine with lots of moving parts. I love my job – every day brings a new challenge. When I was a kid, the Brethren used to talk about “Satan’s printing presses,” and we were banned from reading the Sunday Star-Times, so it’s pretty surreal that I’m now one of the people in charge.

You are speaking at the DECULT conference. Why did you want to be part of that?

Events like this are really important for networking and support. When I meet people who grew up in Gloriavale or the Jehovah’s Witnesses, for instance, there’s so much common ground. There’s a really strong bond among survivors of cults, and the more we work together, the better – to make it easier for future escapees and also to advocate for political change. I’d love to see a centralised support agency for religious refugees, and I’m excited to see what other ideas come out of the DECULT conference.

Do you think it’s important that a conference like this has a specific ‘rainbow panel’?

Yes, because rainbow whānau are disproportionately affected by the practices of extremist religious groups. While it’s great that society is generally becoming more inclusive, deeply homophobic and transphobic pockets still exist, even here in Aotearoa. I’m looking forward to discussing a cross-community approach with other panel members.

For any of our readers who have left or are still involved in a controlling religious sect – what is your advice to them?

Be true to yourself, and give yourself time. It takes years to work through the trauma, and I don’t know that it’s possible to ever fully get over it, but you can’t put a price on freedom. And remember, thousands of other people have walked this road before you. Reach out and find us if you need help or advice. The Olive Leaf Network is a great website, set up to help people leave high-demand religious groups.

Craig will be talking about his recently published memoir, Excommunicated, at the DECULT conference, live streamed from Christchurch’s Tūranga Library on 19 and 20 October. Tickets from decult.net

Where You Can Find Help:

Outline: Call 0800 OUTLINE (available 6pm and 9pm)

Lifeline: Call 0800 543 354 or text 4357 (HELP) (available 24/7)

Youth services: (06) 3555 906

Youthline: Call 0800 376 633 or text 234.

If it is an emergency and you feel like you or someone else is at risk, call 111.

Main Photo | David White.