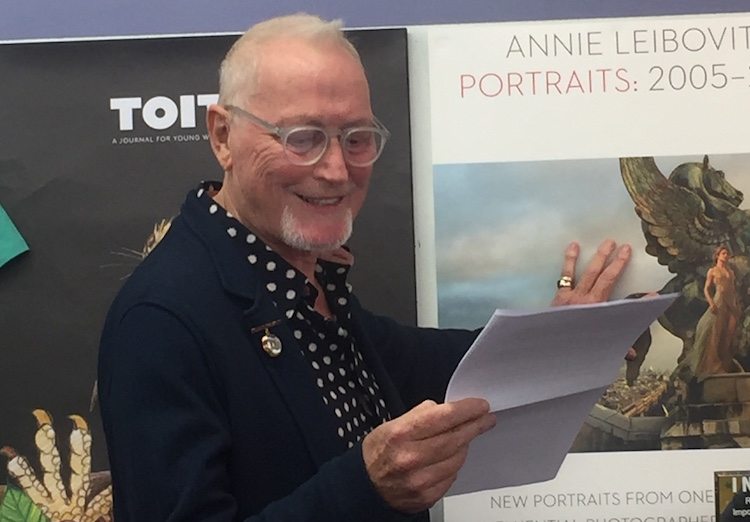

Tim Owen attends the book launch for Dear Oliver, the latest from New Zealand’s most beloved veteran author, Peter Wells held at the Woman’s Bookshop Ponsonby on 21 March. He previews Dear Oliver.

This is a personal story intimately interwoven with the history of colonial New Zealand and the place of the Pakeha in a foreign land, rising from servant status to the comfort of middle class over many decades, many secrets and many sins.

Spanning a century, Dear Oliver is a letter to the youngest member of the family, weaving the years between him and the oldest into one fabric through a treasure-trove of personal correspondence. Oliver is the 8-month-old baby of two lesbian mothers, one of them Peter’s second cousin. Peter’s mother had just turned 100.

Amongst this correspondence is a coming-out letter, penned by Peter to his parents in ’77, delivering both his startling news regarding his sexuality and his decision to change the direction of his studies, as if both were equally weighty. His mother requests that he keep his sexuality a secret from his father; she feels she is somehow to blame.

In opening, Peter laments the forgotten sentiment of the posted letter, the anticipation, the excitement at seeing that little white envelope with the blue score and the stamp with the squiggly black lines impressed over it.

Detailing jagged edges of long-held secrets, Peter lays all bare in this exquisitely presented book with a personal reflection through the eyes of others into many affairs, both private and public. The fact that he and his brother Russel were to leave their sexuality unnamed. Events such as Russel’s diagnoses with HIV in 1988 and the impact it had, being a death sentence at the time.

Photographs and letters detailing the earthquake in 1931, in which 256 people lost their lives, are presented, with insights into how it affected the community, and specifically, his family. The loss of his father, not physically but emotionally, to the mental consequences of war. The 3:40 am call, telling him his mother was dying, and the guilt of not getting to her before she did.

Peter’s life is a life, such as most of us have experienced, up and downs, hardships and challenges, but who among us is brave enough to bare our internal diaries for inspection like Peter has done? Peter leaves no truth untold, not secret unrevealed, no tragedy unwept for.

Dear Oliver is published by Massey University Press.