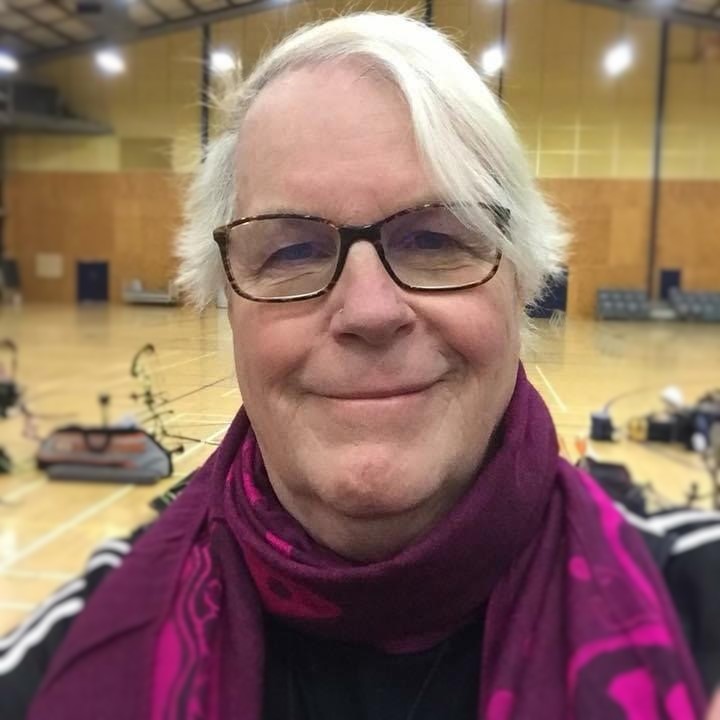

Academic and New Zealander of the Year nominee, Lexie Matheson, gives us her view on what feminism looks like in 2021 and the direction she would like to see it follow.

Talia Bettcher, in a moment of profound superficiality writes, in ‘Feminist Perspectives on Trans Issues’, that ‘the relationship between feminism and transgender theory and politics is surprisingly fraught.’

Those of us who live in the shadowy, often brutal, world at the intersection of shit-stirring and serious intellect, might note that Bettcher is stating the obvious because it is fraught, and we know that.

Don’t get me wrong, Bettcher’s article is an excellent introduction to this troubling topic but it lacks the raw and visceral bloodletting that often accompanies our experiences on the frontline. ‘Enter at your own risk’, it might say, but be prepared to have your humanity mauled and your genitalia examined.

In the savage world of internet trollery, it’s as ugly as it gets.

My journey from middle-class, heterosexual, white, male privilege to vilified, same-sex attracted transwoman is nothing special. I’ve known what I am since I was eight but got lost in a fog of blokery and didn’t come out until 1998. I was a fascinated observer of the effects of First Wave feminism because my Mum rejected it totally. African-American activist Sojourner Truth demanded ‘Ain’t I a woman’ but Mum didn’t want a bar of it. She did value her vote, however, so maybe she wasn’t a totally lost cause.

I did, however, get enthusiastically immersed in the tangled web of the Second Wave. I was drawn to its radicalism, it’s demands for reproductive rights and social equality, its focus on class and its engagement with women of colour. It felt good when shit got real, Proc Thompson got his comeuppance in Albert Park and Stephanie Johnson used it as creative fodder for ‘The Shag Incident’.

Sadly, 60’s feminism got swamped by all the other social movements of the time.

Fittingly, the feminist who has had the greatest impact on my journey, Kimberlé Crenshaw, became active around this time. She opened the door to the Third Wave and concepts of marginalised intersectionality, overlapping social identities and a multiplicity of issues specific to minorities. I remain drawn to the Third Wave’s ‘celebration of ambiguity’ and the idea that ‘it’s possible to have a push-up bra and a brain at the same time.’ Here was a mooring where my feminism was acceptable because, often, it simply wasn’t.

While Third Wave secured feminism in the academy, the fourth brought it ‘back into the realm of public discourse.’

I’ve always been troubled by the word ‘feminism’ because of its assumption of a gender binary that’s ‘for cis-women only.’ The Third Wave revelled in the importance of inclusion, ‘an acceptance of the non-threatening sexualised body and the role the internet can play in levelling hierarchies’. Fourth wave feminists, thank the Goddess, are truly themselves and not just ‘a hand-me-down from grandma.’

Sadly, feminism in 2021 is, for me, more of the same and I can’t see it changing. Gender critical radical feminists (TERFs) will continue to focus their fear-mongering on transpeople and we will push back and put our faith in a government that has promised much but delivered little. It’s odd that ‘gender critical feminism’ seems to have found a home among fundamentalist Christian groups but First Wave feminism grew out of the Temperance Movement, so maybe it’s not so surprising.

My hope is that Fifth Wave feminism will be a distillation of the best of the rest: a strong academy, vivid and influential public discourse, a strong push for equal rights for self-identifying women, and all with a civility that exposes TERFery for the ugly, violent, obtuse movement that it is.

Not much to ask, and it’s what we deserve.

Lexie was due to join Auckland Arts Festival’s level up: an intergenerational discussion panel on Monday 8 March, but organisers are working to reschedule the event due to alert level restrictions. For more details visit aaf.co.nz

Lexie was due to join Auckland Arts Festival’s level up: an intergenerational discussion panel on Monday 8 March, but organisers are working to reschedule the event due to alert level restrictions. For more details visit aaf.co.nz